Abstract

“Cheating” is not about breaking rules — it’s about breaking illusions. It’s only called cheating when the illusion benefits someone outside the default (white, cis, straight, male, able-bodied). AI, like makeup, surgery, or steroids, disrupts who has access to excellence — and that’s what threatens power. This essay explores how accusations of ‘cheating’ — whether about AI, makeup, cosmetic surgery, or steroids — reveal deeper fears of lost authority and disrupted norms. The problem isn’t the tool. The problem is who gets to use it, and whether it threatens the illusion of fairness or authenticity.

This teacher uses a 100% AI

I wonder—if you handed the average teacher a pen and paper, could they write a full thesis without digital assistance? Would their spelling be flawless without spell check? Would their grammar hold up? Could they find credible sources without a search engine, or cite them correctly without a citation generator? Would they be able to explore perspectives beyond their usual frame — beyond their political, cultural, gender, or socioeconomic bubbles?

Ironically, many of the same teachers who criticize students for using AI tools like ChatGPT would likely struggle to write a thesis under those same analog conditions. And yet, they have no problem relying on AI-powered detectors to catch supposed “AI-generated” work — proving, in a way, that they’re perfectly comfortable using AI when it serves their authority. The contradiction is clear: when students use AI to enhance their thinking, it’s “cheating,” but when teachers use AI to police that thinking, it’s just doing their job.

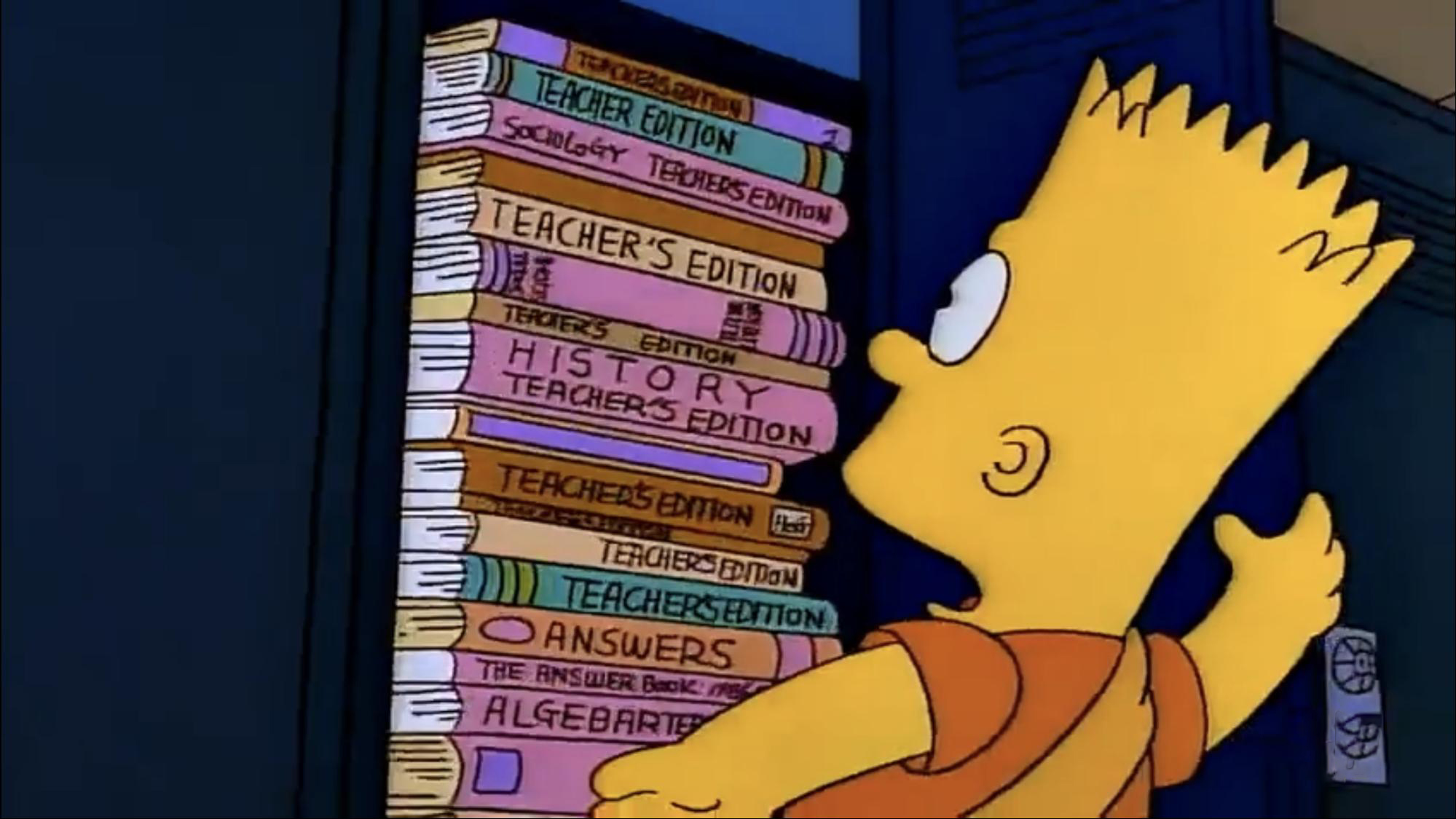

In The Simpsons episode Separate Vocations, Lisa steals all the Teachers’ Editions, plunging the school into chaos as every teacher is left helpless

What motivates me to write this essay is a deep frustration with the hypocrisy surrounding the rejection of AI—particularly in academic and professional settings. Yes, AI can absolutely be misused. I don’t deny that it can be a way to “cheat.” But the blanket condemnation of AI, especially by those in positions of authority, often masks a deeper discomfort with losing control — control over how knowledge is accessed, created, and shared. It’s this hypocrisy that angers me. It’s this hypocrisy that I want to focus on.

The idea that AI is just a shortcut for lazy people? That’s not just wrong — it’s a dangerously lazy take in itself. I want to challenge that belief. I don’t believe education is about feeding students the “right” answer. It’s about helping them learn how to find answers, how to think, how to question — and AI can be an incredible tool for that. Rather than punishing students or (in extension of that) workers for using AI — failing them, excluding them — we should be asking how these tools can be used meaningfully and ethically. Yes, I can imagine situations where AI use crosses into dishonesty, and I’ll address that. But before diving into those distinctions, I want to examine the resistance itself — the suspicion, the moral panic — which echoes older systems of control.

Fear of AI

What drives much of the resistance to AI, I believe, is fear—specifically, the fear of losing control. There's an expectation that what we read or consume should feel human, should sound like someone speaking directly to us, and if it's not, we want it clearly labeled. But beneath that expectation is something more fragile: the need to feel in control of the encounter, to know who or what we're engaging with. People are terrified of being fooled — of mistaking something artificial for something authentic.

This fear of being “fooled” reflects a deeper desire to maintain authority over knowledge and perception — especially when that authority has historically belonged to dominant groups. And when those in power feel that their tools for categorizing, judging, or disciplining others no longer work, they panic. This desire for control, for legibility, surfaces in other areas too — particularly in how we respond to bodies, appearances, and performances that defy expectations.

Makeup or fakeup?

This same fear shows up beyond AI — in how people react to anything that disrupts their sense of what’s “real.” Take, for instance, the straight man who criticizes a makeup artist. It’s not the makeup itself that bothers him, but the fact that the illusion challenges his authority to know, to judge, to categorize.

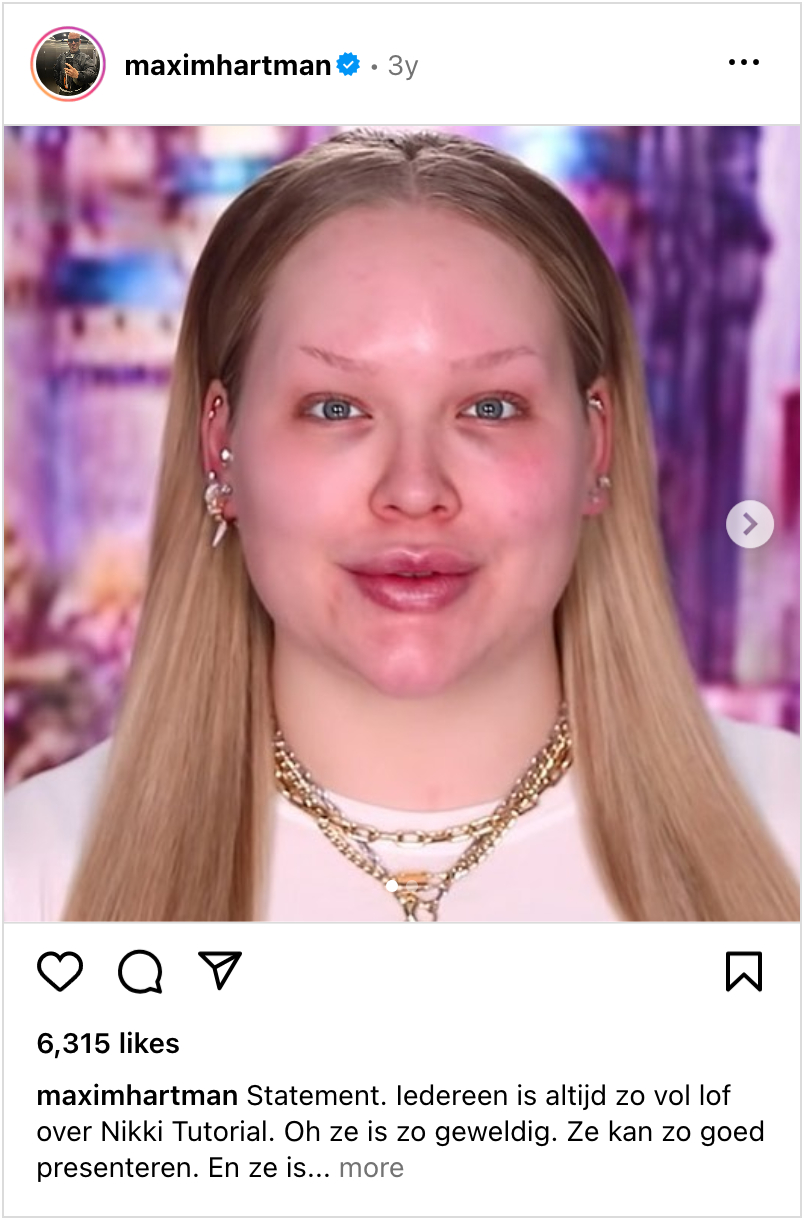

In an Instagram hate post, epistemically arrogant, average white Dutch middle-aged man Maxim Hartman launched a tirade against Nikkie de Jager — One of the Netherlands’ most successful makeup artists and social media icons. His rant relied on misogynistic clichés so overused they should come with a warning label. From racist slurs comparing her to “Polish prostitutes,” to dehumanizing labels like “nonbinary creatures,” to fear-mongering slogans like “protect the children,” the post was a greatest hits of reactionary anxiety. But what struck me most wasn’t the inflammatory language — it was his closing line: “All makeup is fraud.”

And there it is: the ancient accusation that wearing makeup is inherently deceitful, that it’s a lie told by people—mostly women and queer people—about what they “really” look like. But why does that notion hold so much emotional charge for men like Hartman? Nobody owes you their body. Nobody owes you their honesty. No one is obligated to present themselves without makeup just to educate your child — or to maintain your illusion of visual legibility. Wearing makeup is not an act of deception; it’s an act of self-authorship. So what exactly is being threatened here?

Perhaps it’s the loss of control. Perhaps, deep down, what enrages men like Hartman is that makeup dismantles the visual cues they’ve come to rely on to assert dominance. “Honesty” becomes a weapon — used to demand access, to “out” people, to restore the shaky foundations of patriarchy. What they want isn’t truth—it’s clarity. They want to look, and know. They want to categorize, to clock, to confirm. Or is it something more fragile — like the fear of attraction to someone outside their norm? A trans woman gave you a boner once, and now you think you're gay?

Makeup challenges deeply embedded systems of power. It queers visibility. It disrupts class, race, and gender expectations by allowing people to craft appearances aligned with upper-class aesthetics, white beauty standards, or specific gender presentations. That transformation threatens the social function of those markers as tools of separation—tools that have historically benefitted patriarchy, white supremacy, and heteronormativity.

This isn’t just about makeup. It’s about who gets to control the narrative of bodies, beauty, and truth. And that narrative is always policed more harshly when it’s written by those outside the default.

Straight men fear makeup because it threatens to reverse the gaze — they become the object, the misread, the fooled—and that feels humiliating in a way that reveals just how deeply they’ve equated queerness, femininity, and ambiguity with shame. But when queer people use these same tools of “deception,” it’s not about tricking—it’s about surviving, reclaiming authorship, and resisting the demand to be legible on someone else’s terms.

Makeup, as we’ve seen, is treated as deceit when it exceeds or queers expectations. But this suspicion doesn’t stop at brushes and contour — it extends into flesh itself.

The edited body

Take billionaire shapeshifters like Elon Musk and Kim Kardashian. Musk might refuse to call his trans daughter by her chosen name, but when it comes to reshaping his own body, he’s fluent in the language of change. Hair transplant. Facelift. Allegedly, even a botched penile implant — rumors that sound like cyberpunk body horror. All of it is gender-affirming care. Think about it. A man changes his body to match how he wants to be perceived. It’s not mutilation when he does it—it’s a “glow-up.”

BREAKING: Azealia Banks confirms Elon Musk’s cyber-schlong malfunctioned

Kim Kardashian lives in a similar kind of contradiction. Her body has been meticulously sculpted, edited, and rebranded again and again, but the transformation is coated in silence and wrapped in claims of “natural beauty.” I don’t necessarily think she owes anyone an explanation. But I do think her silence isn’t neutral. It protects a fantasy that beauty is innate, effortless — that some people are just born exceptional. When Club Kid icon Amanda Lepore surgically transforms her body, she leans into the artifice. She performs it. She makes it visible. Kim, on the other hand, insists on being read as real. And realness, in this context, is a weapon.

Kim showing x-rays like TSA thought she smuggled the moon in her jeans

I catch myself in this contradiction too. I edit photos. I love artifice. I believe in transformation. What bothers me isn’t surgery, or filters, or digital retouching — it’s the way access to transformation is policed. When cis men and women undergo these changes, they’re seen as self-investments, power moves. But when queer people do the same, we’re pathologized. A cis man reshaping his body isn’t “lying,” he’s optimizing. A trans woman doing the same is suddenly accused of deception, mental illness, or worse. The transformation is the same. What changes is the frame.

Study I: Hypermasculine Ideal meets Algorithmic Androgyne. An exploration of digital identity collapse through facial distortion and ego mirroring. 2025, JPEG.

Study II: ‘Jizz Taco Emerges.’ Early iterations of the persona unfiltered by societal binaries. Michiel recedes into post-human mythos. 2025, JPEG

It’s not just about who transforms — it’s about who’s allowed to do it without scrutiny. That’s why I resist calling Kim Kardashian dishonest just for curating her image. I admire her craft. But next to someone like Amanda Lepore or Nikkie de Jager — who turn disclosure into performance — Kim’s denial becomes part of the performance too, whether she admits it or not. Maybe the difference is that her image upholds a narrow, heterosexual, binary ideal, while theirs destabilize it. The same tools. Very different stakes.

What frustrates me isn’t the edits. It’s the hypocrisy. It’s the fact that billionaires like Musk get to rewrite their bodies while mocking others for doing the same. That cis people can undergo the exact same procedures and never be asked what they’re trying to “escape.” That their silence is seen as elegance, while ours is framed as fraud. Everyone edits. Everyone performs. But not everyone gets to do it without consequence.

If gendered transformation through surgery invites scrutiny, so too does physical transformation through steroids—especially when it’s men reshaping their bodies in ways that reveal how fragile the idea of ‘natural excellence’ really is.

Natty or not?

So to be fair to the boys: let’s talk about the “natty or not” debate in bodybuilding — whether using steroids is considered cheating. The logic goes like this: a truly earned body is one built without enhancement. Anything else is fake, a shortcut, a lie. But again, the deeper question isn’t about fairness. It’s about maintaining the illusion that all bodies start from the same baseline, that success is purely a result of effort. But that’s not true.

Bodies are not equal. The assumption that they are is a supremacist belief contested by plus-size people, disabled people, and trans people. Our physicality disrupts the eugenic fantasy of the able, muscled, male body as biologically supreme. That fantasy still lingers in modern ideals of ability, beauty, and worth. “Natural” becomes shorthand for “acceptable,” for “earned.” But if we scrutinize that standard, it quickly collapses.

Take Ozempic, for example—a diabetes drug increasingly used for weight loss. Like steroids, it’s often denied or hidden by those who use it, even as cultural pressure demands they achieve the results it offers. What unites these substances is the contradiction they expose: we’re told we should want to look like GI Joe or a runway model, but actually using tools to get there is seen as cheating. Why? Because it undermines the myth that these bodies are the product of discipline, grit, or superior genetics — not privilege, access, or pharmacology.

Ozempic exposes a catch-22: on one hand, people are punished for not conforming to the thin ideal; on the other, they’re shamed for taking pharmaceutical shortcuts to reach it. It’s not just that we worship the default body — it’s that we expect people to both possess it naturally and aspire to it relentlessly. It’s a morality play disguised as a health discourse: use the drug, and you're vain; refuse it, and you're lazy. The punishment is built into both options, and the ideal remains untouchable either way.

Steroids and Ozempic aren’t cheating. They’re an acknowledgment of limitation—and a desire to transcend it. To me, that’s not dishonesty. That’s innovation. It’s no different from designing a racecar: you optimize for performance.

Intermezzo: The Common Thread

I’ve been comparing AI to makeup, cosmetic surgery, and steroids. All have been accused of being “cheating.” But they’re not. They’re tools of transformation — tools that offer freedom to people whose default existence is already constrained. They shift power. They destabilize dominant norms. And that makes them threatening. I could write case studies for days — Auto-Tune, porn, vaccines, birth control, filters. All labeled ‘cheating.’

The real issue is not cheating. It’s control. People want to control what they witness. They want full disclosure — not to understand, but to dominate the context. To feel safe in their categories. But transformation disrupts that. It queers certainty. It resists legibility.

And that’s the radical potential of AI, too. It allows people to express, imagine, and build in ways previously unavailable. Sure, this essay used AI — just like your GPS, your spellcheck, your camera filter, and half your personality online. Enhancement is the norm, not the exception. AI replaces labor. And labor creates surplus value. That’s why we’re drawn to it. Because it lets us make more, faster, better—with less effort. And that frightens people. Not just because it challenges systems of labor and value, but because it erodes the illusion that some kinds of effort are more “authentic” than others.

Reading Mythologies by Roland Barthes, I often felt like he was describing the very systems I’m trying to challenge. Barthes talks about how myths are not lies, but stories dressed up as “natural” — ideas so normalized we stop seeing them as ideas at all. The “natural body,” the “authentic self,” the “real student” — they’re not neutral categories. They’re ideals, manufactured and policed to keep certain people in power. Barthes didn’t care whether something was true or false; he cared about why certain things are treated as obviously true, and who that truth serves. In my essay, I’ve been calling these accusations of “cheating” what they really are: panic over people refusing to play by rules that were rigged from the start. Barthes would’ve called it myth. And once you see the myth — that what’s considered natural is often just the dominant aesthetic, the dominant story—you can’t unsee it. That’s what I’m trying to do here: show the seams in what we’re told is seamless. Disruption is not deception. It’s a way out.

Reading Mythologies didn’t just help me name what I was seeing — it gave me permission to look differently. Once you realize that the “natural” body is a story, not a baseline, everything opens up. If dominant norms are upheld through repetition and policing, then maybe subversion begins in doing things differently — refusing to apologize for artifice, for enhancement, for desire. That’s what drew me to these tools — AI, makeup, steroids — not as hacks or cheats, but as invitations. Each one lets you bend reality a little, test its limits, write your own version. So the question isn’t “Is it fake?” but “What does it make possible?” I don’t want to just critique the myths — I want to play with them, push them, break them open. And in doing so, sketch out what else a body, a self, a society could be.

Prompt: Generate possibilities beyond current societal norms

What would a society look like if tools like AI, makeup, or steroids were openly embraced as forms of self-expression and resistance? Many of the case studies I’ve discussed reveal how these tools, when removed from systems that serve the patriarchy, often find fertile ground in queer communities — becoming not just methods of transformation, but of subversion.

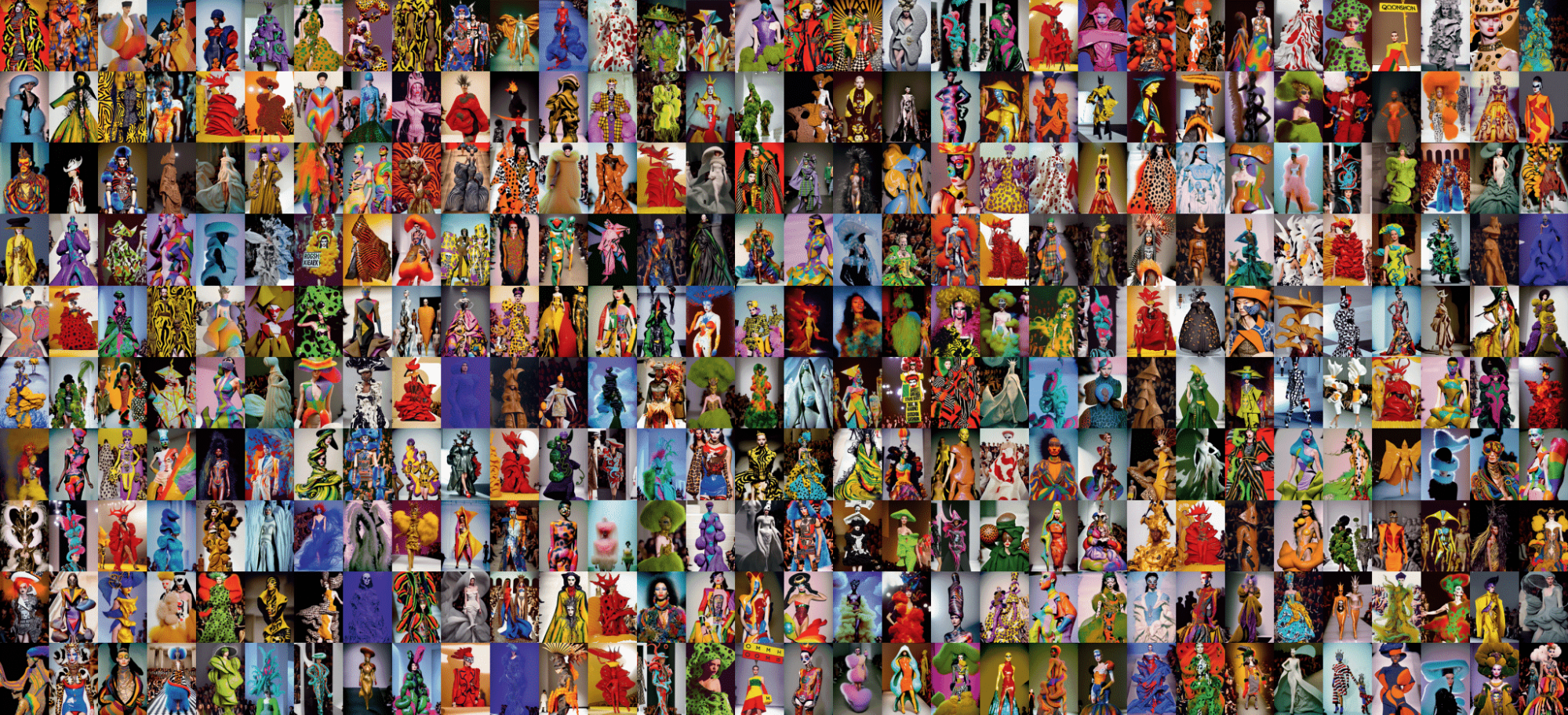

Songwriter and performer MIKEY. Woodbridge’s LATENT COUTURE is a powerful example of this. The project consists of 555 AI-generated “fashion statements,” remixing the artist’s photographic archive into hybrid couture pieces that blur the boundaries between fashion, fantasy, and self-portraiture. Emerging from the latent space of machine learning, each image becomes a speculative garment — part body, part glitch, part dream. The work doesn't just showcase what AI can generate, but what queer subjectivity can become when mediated through digital tools.

MIKEY. Woodbridge’s LATENT COUTURE proves a look isn’t just a meme—it’s a manifesting spell. AI meets icon, and every image whispers: this person is possible.

Still, I wonder: are works like LATENT COUTURE really about imagining new possibilities — or are they more about remixing what already exists, exaggerating it until it becomes something else? Yes, they look like fashion, but what is their function outside the speculative? These garments can’t be worn. They exist mostly within digital or institutional spaces: the Instagram feed, the white cube. They seem to feed a conversation about AI’s aesthetic potential, but what is their role beyond that? they risk becoming CARICATURE COUTURE — not inventions of new worlds, but hyperreal distortions of the ones we already know.

Woodbridge has argued that each “fashion statement” imagines a possible person. That idea resonates with me. In my own project Fwd: My pro-lgbtq+ ex Zac is VJ-hunk, I used AI to alter photos of myself into a drag persona. Not just for spectacle, but to create a usable identity — one that queers the version of myself I had once constrained to appear straight. I treated AI as a tool of narrative construction, similar to how branding creates coherence for a company. This persona became a way to escape limitations I had internalized, and a way to open up new modes of working. In this sense, AI wasn’t just speculative — it was instrumental. A way of doing identity, not just imagining it.

Jizz Taco: not a persona, but a digital possession. Face filters on max, gender norms in shambles, and reality politely asked to leave

That’s where I see a crucial step: speculation is powerful, but it matters what comes after. In MIKEY’s case, the exhibition POLY. A fluid show frames LATENT COUTURE within a collective setting. Context shifts the function of the work—from private fantasy to public statement, from image to gesture. Maybe the true radicality of these tools lies not just in what they can generate, but in how we choose to live with and through them.

Where LATENT COUTURE speculates in the language of fashion and persona, and my own work plays with identity through narrative self-invention, Unionizing the Speculative by designer and design theorist Noam Youngrak Son offers another orientation — one where AI is not just a tool for imagining new selves, but for restructuring collective conditions. They reclaim AI as a site of labor and political imagination, asking what kinds of futures are possible when speculative practices aren’t just individualized fantasies but mechanisms for solidarity, resistance, and structural critique. In contrast to the consumer-facing spectacle of AI-generated beauty or style, their work investigates how algorithmic tools can be co-opted to serve worker-led, post-capitalist, queer-feminist frameworks.

Speculoos biscuits containing AI-generated images—crispy carriers of algorithmic visions. A delicious artifact from Unionizing the Speculative, via d-act.org

What I find valuable here is the insistence that speculation is not neutral — it always serves someone. Whether it’s a couture image that flatters the machine’s aesthetic biases, or a branded persona that opens doors for queer visibility, these acts of speculation sit within power structures. My own project attempts to queer those power structures through self-performance, but Noam’s work reminds me that transformation doesn’t stop at the self. It asks: who builds the models, who profits, who gets erased? In a way, it challenges artists like me — and like MIKEY — to consider how speculative aesthetics can also be grounded in speculative ethics. The fantasy is real, but so are the systems underneath it. What does it mean to unionize imagination itself?

Well, that takes me straight to The Matrix.

The sky is not blue

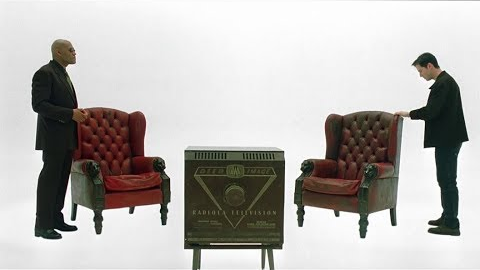

Morpheus and Neo stand in “the Construct,” a blank white loading program where anything can be simulated. Neo struggles to accept that his world—the people, the buildings, even the steak—was all a computer- generated illusion. Morpheus challenges him: “What is real? How do you define ‘real’?” He answers his own question: if “real” is what you can see, smell, touch, or taste, then “real” is nothing more than electrical signals interpreted by your brain.

When Morpheus said: I came to realize the obviousness of the truth. That part

This scene is useful not just for its sci-fi drama, but for how it frames reality itself as an unstable category. If your brain only ever experiences simulations of the world — interpreting data through nerves converting it into meaning — then even illusions can feel real. The blue sky? An internal construction. The taste of steak? A neurological event. The essay you’re reading? Still just data filtered by your perception. So when we start outsourcing the question of “what’s real” to AI detectors or authenticity tests, aren’t we just asking another machine to validate a simulation for us?

Let’s push that even further. If a transgender woman turns you on, is she not “real enough”? What makes you pause — is it your body’s response, or the story you've been told about what desire is supposed to mean? If reality is brain-processed sensory input, then her reality is your reality. Same with makeup. Same with steroids. Same with surgery. These are tools that change how we appear, how we move through the world — but the effects are real because the response is real. Your belief about what’s “natural” doesn’t override your nervous system.

In that sense, questioning someone’s authenticity because they use enhancement is like questioning your hunger because the food was microwaved. You're still full. Your senses still responded. The deeper issue isn’t what's real it's who gets to decide what's allowed to count as real in the first place.

Cutting off the phallussy

Before anyone gets clever and twists this into some kind of “your boner defines her womanhood” argument — let me stop you right there. The fallacy I want to smash is the idea that someone’s gender — someone’s transness — can be defined by someone else’s perception. That how you experience another person determines the truth of who they are. It doesn’t. Your senses don’t get to claim ownership over someone else’s reality. That’s not how identity works. And it’s definitely not how reality works—not the kind of reality I’m advocating for.

Throughout this essay, I’ve explored case studies that orbit around claims to truth: Who gets to be seen as honest? Who decides what counts as “real”? I’ve tried to show that the problem isn't transformation—it’s hypocrisy. That what’s often labeled as deception or artifice is actually just someone refusing to play by rigged rules. But here’s the key shift: even when someone is “clockable,” even when they don’t pass according to someone else’s sensory checklist, they are still the gender they say they are. Your perception doesn’t overrule their reality.

I’m not saying passing doesn’t matter socially — it can be a tool, a shield, a survival strategy. But I am saying that passing should never be the litmus test for legitimacy. When a cis man perceives someone as a woman, and then learns she’s trans, the urge to “correct” that feeling reveals the myth at work: the myth that his senses are more objective than her identity. That his brief perception trumps her lived experience. That’s not truth. That’s ego masquerading as logic.

A person’s gender doesn’t require external validation. Your recognition may shape how you treat them — but it doesn’t define them. The truth of someone’s identity lives in their own experience, not in someone else’s ability to detect, approve, or decode it.

Conclusion

Between the critic ranting about AI in a smoothed-over video and the follower nodding smugly in agreement, a hundred algorithms have already done their work. You’re not outside the system. You flip through fashion magazines filled with photoshopped faces and surgically sculpted bodies. It doesn’t stop you from caring about the clothes or the politics. If anything, the fantasy makes it more attractive. It’s beauty. It’s performance. It’s allure. You stream auto-tuned artists — not because their raw voice is sacred, but because the result is transcendent. You might take steroids, or ozempic, or hormones — not because your body failed, but because you want it to reflect who you are and how you want to be seen. Makeup doesn’t just paint a face — it builds a persona. And sometimes, that persona is more real than what came before. These aren’t delusions. They’re tools we already use every day to survive, to thrive, to become. So the question isn’t whether fantasy is real enough. The question is: who gets to use it without being called a liar?

I don’t believe AI is ruining truth or honesty. What ruins that is power without accountability — and the way that power trickles down, turning poor, queer, creative people into enforcers of the very systems that punish them. It’s the same pattern, over and over again: trans people policed by cis strangers, or students accused of cheating by systems designed to fail them. Not because these technologies — AI, surgery, steroids, editing — are inherently wrong, but because their use disrupts a “natural order” that was never natural to begin with. An order built to reward some forms of transformation, and punish others.

That’s what I’ve been tracing: the myths we dress up as truth. The panic that arises when someone breaks the rules that were rigged against them. The refusal to believe in a self that wasn’t authorized by power. But if passing a test—or passing as a woman—depends on someone else’s idea of real, then what does that make truth, except a permission slip?

So no, I don’t believe AI is cheating. I believe the people who hoard power and use it to police others are. And I believe the answer isn’t “the natural.” It’s possibility. Not to gatekeep imagination, but to organize around it. To turn these so-called tools of deception into tools of becoming.

Let them call it cheating. We’ll call it self-determination.